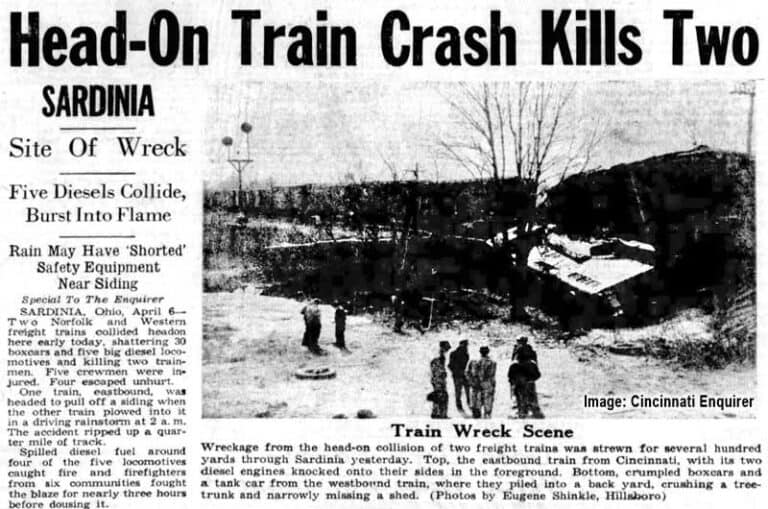

Casey Jones: Brave Engineer or Asleep at the Throttle?

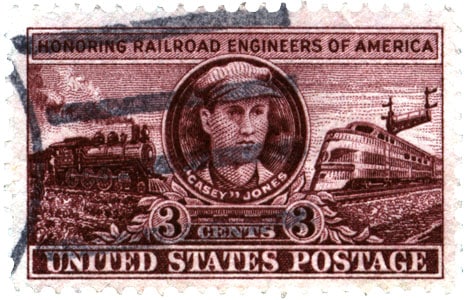

My old pal, Billy Bob Derryberry, and I were sitting around sipping suds and sucking boiled peanuts one summer afternoon when he brought up the subject of Casey Jones, the famous railroad engineer. In the early morning hours of April 30, 1900, John Luther “Casey” Jones became an American legend when he plowed into the back of a freight train that was stopped at Vaughan, Mississippi. The rest, as they say, is history.

Casey Jones was Billy Bob’s hero. He often talked about the bravery Jones exhibited, staying with his engine, knowing that a violent death was rapidly approaching. So naturally, ol’ Billy Bob was ready to take issue at my comment that Casey Jones couldn’t drive worth a damn. “Whadda ya mean?” hollered Billy Bob “Casey Jones was the best engineer the Illinois Central ever had.” “That’s right, Billy,” I said, “had.” “Well, it weren’t easy to drive one of them steam engines,” Billy replied.

Photo via the Water Valley (Mississippi) Casey Jones Museum

“Yeah, you’re probably right,” I said. “They only move in two directions, and you don’t even have to steer ‘em.” “Well, what about all a them levers, ‘n’ valves, ‘n’ gages?” Billy said. “Big deal, Billy,” I said. “You got yer throttle and yer reverse lever. The fireman watched all the other gages. That’s why you always see the engineer with his right arm on the window cushion and his head outside enjoyin’ the breeze while the poor fireman is stuck in that hot cab shoveling coal as fast as he can. Heck, engineers like Casey Jones blew more coal out the smokestack than they ever burned in the boiler.”

Well, I may as well have been talking to a brick wall. Billy Boy was as stubborn as a mule, and not much smarter; nothing I could say would change Billy’s opinion of Casey Jones. Billy was told all his life that Casey Jones was a hero, and not even cold hard facts would convince him otherwise. But I know that you, dear readers, believe in facts. And if you’ve read any of my articles, you know I always tell the truth. I’m the proverbial Eagle Scout, someone you could trust your college-aged daughter to spend the night with at a Motel 6. So, in the vernacular of the Deep South, here be the facts about Casey’s ride into eternity.

On the night of April 29, Casey Jones arrived in Memphis, Tennessee at the end of his regular run with a northbound passenger train. After checking in with the Memphis trainmaster, Casey was asked if he would take the southbound Chicago-New Orleans “Cannonball” from Memphis to Canton, Mississippi, 188 miles south. Although Jones would be “doubling out,” which meant he would get no sleep between runs, the extra money was always welcome.

The “Cannonball” arrived late, and Jones was 95 minutes behind schedule when he left Memphis. By the time he reached Vaughan, he was only two minutes behind schedule. The timetable for the run south from Memphis was based on an average speed of 35 miles per hour. Jones had to be traveling at least 75 mph to make up those 93 minutes because at each station stop along the way he could not leave the station before the scheduled departure time.

As Casey was smokin’ the rails on his way to Vaughan, he was unaware that two southbound freight trains were moving in and out of the Vaughan siding to allow two northbound passenger trains and one southbound passenger train to get by. This switching easily could have been completed before Casey’s Cannonball reached Vaughan, but there was a minor problem. Freight train No. 72 busted an air hose (which sets all the brakes on the train), as it was moving off the main line and into the siding. Four cars and the caboose were still on the main line and Casey Jones was barreling toward them at 75 miles an hour.

Photo by Ralph Mayer, posted to Flicker and used via CC by 2.0 license.

But this sort of thing often happened in the early days of railroading, and there were rules in place to prevent just the kind of accident that was about to happen. Earlier, a flagman from one of the freights had gone 3,000 feet up the tracks and placed a “torpedo” on the tracks. The flagman then walked another 500 feet up the track and stationed himself with his lantern where any oncoming train could see him.

The torpedo was a little package of explosives that was clipped to the rail. When an engine ran over the torpedo, it would make a loud bang, and warn the engineer and fireman that something was ahead of them fouling the track. Upon striking a torpedo, the engineer was required to quickly bring his train to a complete stop and then proceed at restricted speed, prepared to stop within half the distance to an obstruction or equipment on the track ahead.

Casey went by the flagman, who was frantically waving his lantern, at 75 miles an hour and chewed up those 3,500 feet of track in about 30 seconds. Now, thirty seconds really is a long time. A lot longer than the ten-count my mother used to give me before she started walloping me. Try it. Count “one thousand and one, one thousand and two, one thousand and three,” to one thousand and thirty and see if you have enough time to run down the stairs and out the front door before your mother can reach you. (WARNING, Children! Be very careful if you try this at home. It only works if your mother is behind you, not in front of you.)

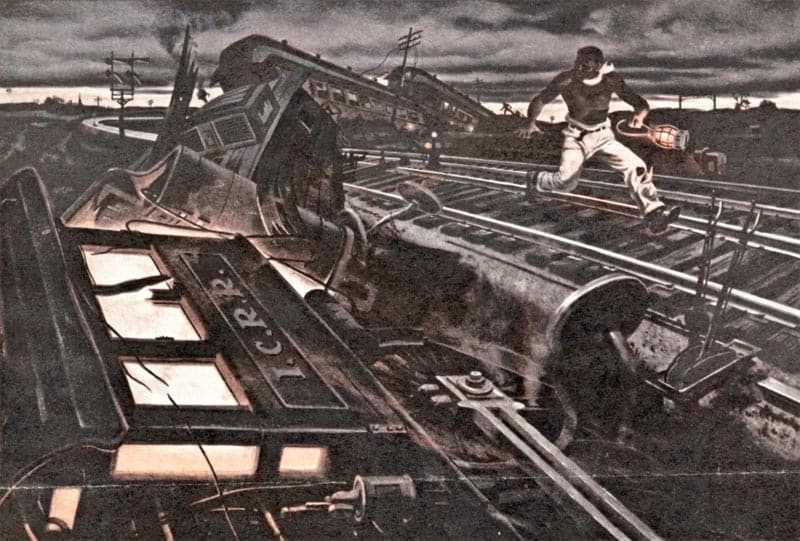

Casey’s fireman, Sim Webb, saw the rear lights of the freight train’s caboose about 100 yards ahead. Casey couldn’t see the lights because they were entering a sharp left-hand curve. Sim yelled at Casey and Casey told him to jump off the engine as he put the brakes into emergency. Sim jumped; Casey didn’t.

Illustration by Geoffrey Biggs, via the Library of Congress

The engine plowed through the caboose, a carload of corn, and a carload of hay before coming to a stop. No one on the freight train was injured. Thirty-five minutes later, Sim Webb regained consciousness on the floor of the Vaughan station where rescuers took him after finding him lying next to the tracks. Casey Jones never came to and was pronounced dead at the scene; he was the only fatality. Casey was two minutes behind schedule when he bought the farm in Vaughan, Mississippi.

Was Casey asleep at the throttle? He didn’t see the flagman, even though the tracks were straight as an arrow a mile and a half in front of the flagman. He didn’t hear the torpedo, which is as loud as a 12-gauge shotgun. And he didn’t sound the whistle as he passed the whistle post for Vaughan station. It was 3:52 a.m., and Casey had been up for almost 24 hours.

For all we know, Casey could have been sitting in the engineer’s seat, eyes wide open, jaw firmly set, a perfect picture of concentration, and sound asleep. It happens to the best of us. It’s called the “1,000-yard stare,” and this writer experienced it many times in his former life while driving home after an “all-nighter” at the power plant. One minute you’re pulling out of the parking lot, and the next minute you’re pulling into your driveway, and you don’t remember anything in between.

Now, Billy Boy said I was too hard on Casey. You decide. Casey Jones was an engineer for 10 years, and during that time was suspended a total of 145 days, including one suspension for colliding with the rear of another train. He ran through open switches twice; he struck a flat car in a siding; he failed to stop for a flagman protecting a work train; he left a switch open, causing another train to run into a siding. These patterns of behavior, and these antecedents, clearly indicate that Casey’s wreck on April 30, 1900, was no accident.